The Mysterious Magic 9

The Magic 9 is a newer form with uncertain origins. The idea for the rhyme scheme is rumored to have sprung from the rushed misspelling of the famous incantatory exclamation: abacadabra!

Structure of the Magic 9 Poem

Requirements of the Magic 9 form:

– Comprised of a single nine-line stanza

– Must follow the rhyme scheme: abacadaba

– No restrictions on line length, meter or subject matter

Tips and Techniques

One way to get started is to make a list of end words.

To do this form correctly you’ll need:

– 5 a end rhymes

– 2 b end rhymes

– 1 c end word

– 1 d end word

Determine what kind of end rhymes you’d like to use. Click here for a handy guide on the different rhyme types used in poetry.

First try single-syllable end rhyme words, and then expand to two or even three-syllable words. Consider how these changes feel and how each possibility resonates within the structure of the form.

Now brainstorm around your favorite end rhyme clusters, looking for meaningful ways of bringing them together.

Keep it loose at the beginning and let the creativity flow. Your internal editor is not allowed in this free-flowing creative space, so don’t stop to judge or think too critically–that’s what revision is for.

An Original Magic 9 Poem

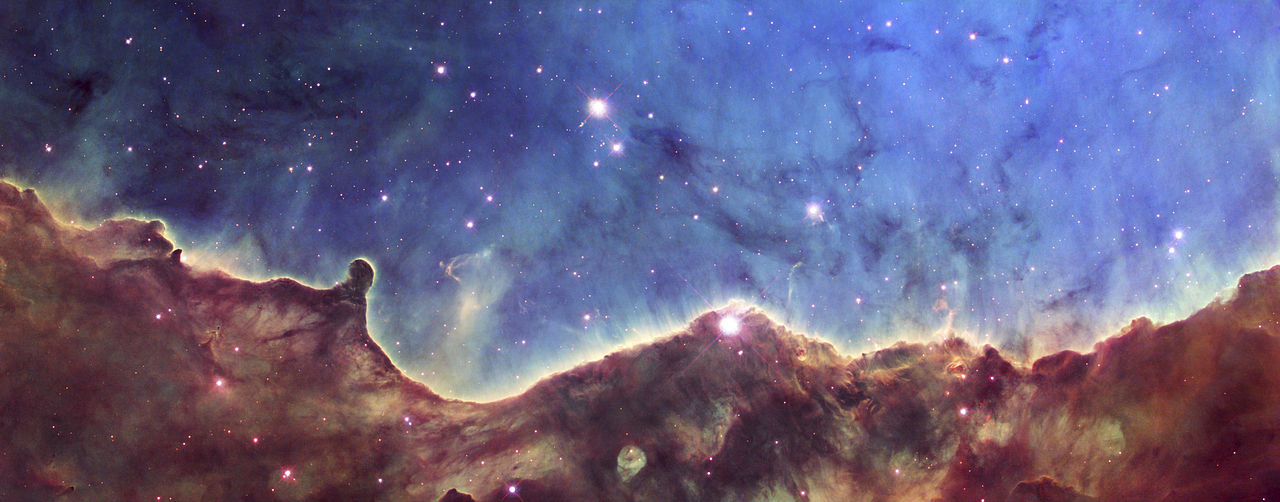

The Stargazers

Away from the glare of the city’s light,

We follow the firefly’s flash.

Abandoning the screens that so narrow our sight,

We trace the heavens for our favorite constellations.

With galaxies and gods, all going ’round in our flight,

We lay down our blanket in a hidden patch of prairie.

In this brilliant darkness, our vision’s set right,

As the dazzling meteors slash

Across the impossible night.

Links to Online Resources:

Types of Rhyme – Daily Writing Tips

~Magic 9 Revisited~

Rather than creating a new poem in the Magic 9 form, I thought I’d share the lyrics to a song I wrote using The Stargazers as a jumping off point. I often look for ways to use formal poetry as a springboard into songwriting.

Escape to the Cosmos

The city at night is a lovely sight,

But the lights can strain your eyes.

I know of a grove off a dark country road.

Why don’t we go for a ride?

We’ll slip away when the daylight fades

And the stars begin to shine.

The clouds have all cleared, and the moon’s not too bright.

We’ll escape to the cosmos tonight.

Far from the bars, the streetlights, and cars,

We’ll lay our blankets down,

Trace the constellations from our bed in the weeds,

And share all the wonders we’ve found.

We’ll slip away when the daylight fades

And the stars begin to shine.

With galaxies and gods, all goin’ round in our flight,

We’ll escape to the cosmos tonight.

The fireflies flash, the meteors dash

All across the impossible sky.

We’ll slip away when the daylight fades

And the stars begin to shine.

In this brilliant darkness, our vision’s set right.

We’ll escape to the cosmos tonight.