Introduction

A unique experimental form born of the mashup of eastern and western poetic traditions, the Haiku Sonnet combines the syllable count and three-line stanzaic structure of the English Haiku with the fourteen-line structure of the sonnet. I first learned of the form –and many of the forms collected for this challenge– from David Lee Brewer at Writer’s Digest, but the form appears to be an invention of Chicago poet David Marshall.

David Marshall on the Haiku Sonnet

Conceptually, it’s an attempt to wed two like and unlike forms. To me, the sonnet seems the quintessential western poetic form, defined by the order and rationality of its problem-resolution organization. Depending how you see it, the haiku might be just as organized—haiku certainly have strong rules and conventions. Because haiku can rely, just as a sonnet does, on a sort of reversal—a “volta” in sonnets, a “kireji” in haiku—they may be distant cousins. However, haiku are eastern, and, where sonnets are rational, haiku are resonant. Where sonnets solve—or attempt to solve—haiku observe.

David Marshall – Haiku Sonnets

A Haiku Sonnet by David Marshall

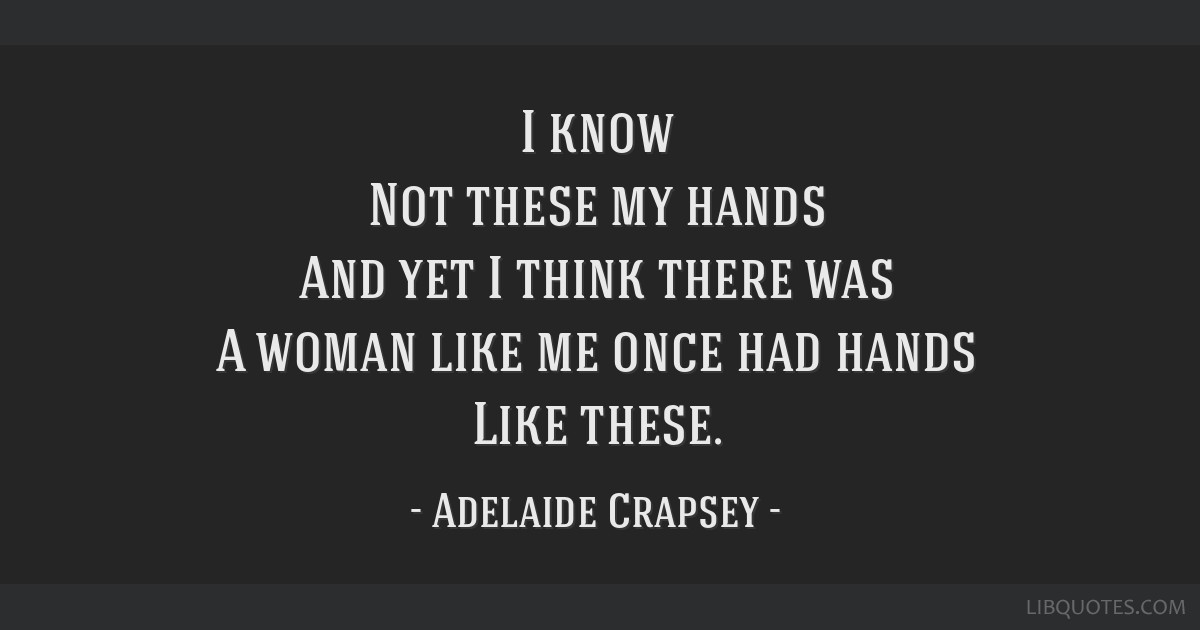

Remembering

I remember winter

now that it’s here—the next word

in a song, a plea

for love you forget

until a character speaks.

Now I remember—

outside this window,

one leaf clung all winter. Wind

set it fluttering

like a hummingbird.

Its sociable flicker was

like life. One day

it flew away, and I thought—

it wouldn’t ever come back.

Requirements of the Form

Structure

– Four three-line stanzas (tercets) followed by two-line stanza (couplet) for a total of fourteen lines

Content

– Written in the present tense

– Syntax may be incomplete to maximize power of brevity

– Refers to time of day or season

– Focuses on a natural image

– ‘Show, don’t tell’ approach

– May contain a ‘volta’ or turn of thought

– Captures essence of a moment

– Aims at sudden insight, spiritual illumination

Syllable Count

– Begins with a sequence of four tercets with a syllable count of 5-7-5

– Ends with a couplet with a syllable count of either 5 or 7 syllables per line

Meter

– No meter

Rhyme

– Unrhymed

Requirements Breakdown

[Line 1] 5 Syllables

[Line 2] 7 Syllables

[Line 3] 5 Syllables

(repeat for lines 4 – 12)

[Line 13] 5 or 7 Syllables

[Line 14] 5 or 7 Syllables

An Original Haiku Sonnet

Among Cottonwoods

The autumn wind blows–

the storms of summer did not

drown the cottonwood.

From the hollow trunk,

monarchs fly away from death

and the coming frost.

They will return when

the soft white snowdrifts of seeds

burst forth in April.

The artist seated

at the roots will have to wait

to carve the soft wood.

Among cottonwoods,

the soul climbs and reaches out.

Links to Online Resources

Haiku Sonnets – David Marshall

Haiku Sonnet – Writer’s Digest